1 Introduction

Additive manufacturing (AM) is a rapid manufacturing technology of producing near-net shape structures directly from CAD models by adding materials in a layer-by-layer method [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Compared to powder-bed-based technology, such as selective laser melting (SLM), wire feeding AM has a higher deposition rate, a larger forming scale and a relatively low cost [7, 8]. Such advantages make it become a potential technology for producing large, full-density and high-quality near-net shape structural components in the aerospace industry. In all metallic materials, titanium alloys have received prime attention in AM because of their broad applications in industry, high cost of manufacturing and long lead time [1, 9]. Ti-6Al-4V α + β alloy is the most widely used titanium alloy in the world due to its excellent properties, such as high strength-to-weight ratio, superior fatigue resistance and corrosion resistance [1, 10]. Especially, it has become one of the key materials for the airframe structural components in the aerospace industry.

Because of large temperature gradient (G) and rapid solidification rate (R) in metal AM process, the deposited Ti-6Al-4V generally possesses coarse columnar β grains (CGβ) with a strong 〈001〉 solidification texture [11,12,13], which results in anisotropic mechanical properties [2, 14,15,16]. Especially for wire feeding AM, the size of epitaxial growth CGβ can reach several millimeters in width and dozens of millimeters in deposited direction [17,18,19], which are undesirable for aerospace applications.

Achieving a completely equiaxed β grains (EGβ) to optimize the mechanical properties of titanium alloys during AM process is a huge challenge [20]. Several methods have been developed for this purpose generally. Firstly, adding grain refining solute and nucleant particles into the alloys to enhance the heterogeneous nucleation during solidification can reduce the width of the CGβ and promote the formation of EGβ [16, 21], which is based on the grain refinement method for casting alloys. Because of the variation of the alloy compositions, the properties of the alloys will be changed. Secondly, Todaro et al. [22] employed high-intensity ultrasound to vibrate molten pool thereby destroying the dendrites and increasing the stirring and diffusion effect. The complete transition from columnar β grains into fine equiaxed β grains has been achieved in additive manufactured Ti-6Al-4V samples by laser powder deposition. Thirdly, interpass deformation, including interpass rolling [23] and interpass machine hammer peening [24], can break coarse CGβ and refine β grains, which is based on the experience of wrought alloys. However, this method makes AM system become more complex. Fourthly, Li et al. [17] developed a method named hot-wire arc additive manufacturing to preheat the wire and reduce the arc heat input, and finally obtained a part consisting of EGβ and short CGβ. This method has been used in the welding of titanium alloy to avoid the formation of coarse CGβ [25].

Recently, Kovalchuk and Ivasishin [26] invented a newly coaxial electron beam wire feeding additive manufacturing technology (CAEBWAM), named xBeam 3D Metal Printing. It has been reported that the controllability of deposition parameters and high cooling rate prevented formation of rough CGβ and promote the formation of EGβ. This technology may become an entirely novel method to improve the microstructure and mechanical properties of Ti alloys in AM. However, detailed investigation on the microstructure evolution is still limited.

In the present work, a structure composed of 2-bead and 5-bead walls of Ti-6Al-4V alloy has been fabricated using CAEBWAM technology. A large region of fine EGβ and isotropic tensile properties was obtained. The formation mechanism of EGβ was further analyzed.

2 Experimental

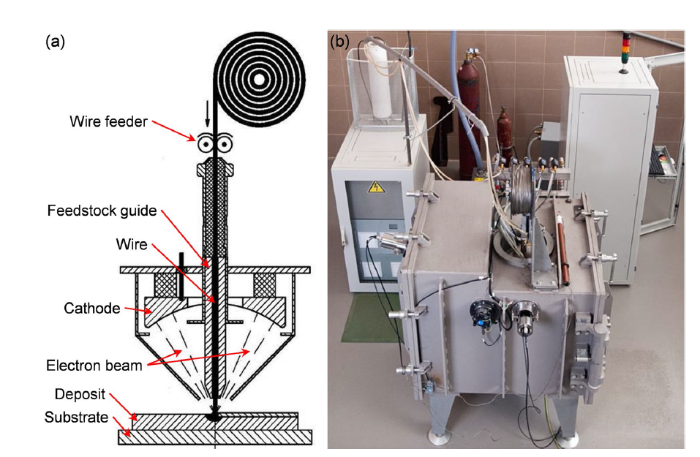

In the present study, the employed xBeam 3D Metal Printer consists of a hollow conical electron beam gun with a maximum power of 18 kW, a working chamber with an operating vacuum of 5 × 10-2-5 × 10-1 mbar, an automatic wire feeder and a three-axis numerical control working table. The schematic diagram and the machine are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Coaxial electron beam wire feeding additive manufacturing system: a schematic diagram, b machine (xBeam 3D Metal Printer)

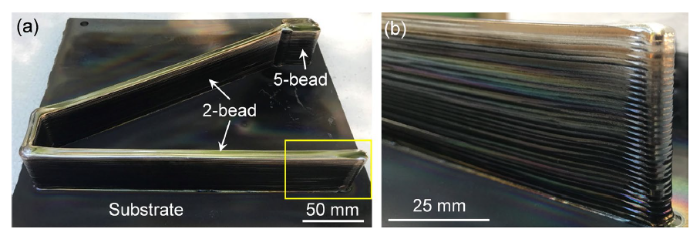

The Ti-6Al-4V wire with a diameter of 3.0 mm is used as raw material. A structure composed of 2-bead wall with a dimension of Y × Z ~ 9 mm × 51 mm and 5-bead wall with a dimension of X × Y × Z ~ 40 mm × 21 mm × 51 mm are built on a polished hot-rolled Ti-6Al-4V substrate with a dimension of 300 mm × 300 mm × 14 mm, where X is travel direction, Z is the building direction, and Y is vertical to X and Z. The employed power is 6 kW, the wire feeding speed is 17 mm/s, the travel speed is 18 mm/s, overlap is 4 mm, and single layer thickness is about 1.5 mm. The deposition strategy is two-way “s”-shaped reciprocating motion. The as-deposited structure presents a good shape and surface, as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Outside view of the as-deposited structure: a overall view, b enlarged image of the squared region in a

The deposited structure together with the substrate is subjected to a series of heat treatments at 650 °C for 1 h followed by air cooling, 920 °C for 3 h followed by gas cooling and 540 °C for 4 h followed by air cooling. The chemical composition of the deposited structure is listed in Table 1. The β transus is about 985 °C. Tensile test specimens are taken from 2-bead region in X and Z directions. Tensile test is carried out using an AG-5000A machine at room temperature with strain rate of 0.005/min and 0.05/min before and after yielding, respectively, according to ASTM E8/E8M-16a. Microstructural observations are carried out on a Leica DMi8 optical microscope (OM). Crystal orientation and tensile fracture surface analyses are carried out on an FEI Quanta 450 FEG scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with electron back-scattered diffraction (EBSD) detector, and the EBSD data are then analyzed by a OIM software. The specimens for OM and EBSD characterization are electro-polished and then etched.

Table 1 Chemical composition of the deposited structure (wt%)

| Ti | Al | V | Fe | O | N | H | C | Y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bal. | 6.26 | 4.25 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.0055 | 0.0014 | 0.0091 | < 0.005 |

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Tensile property

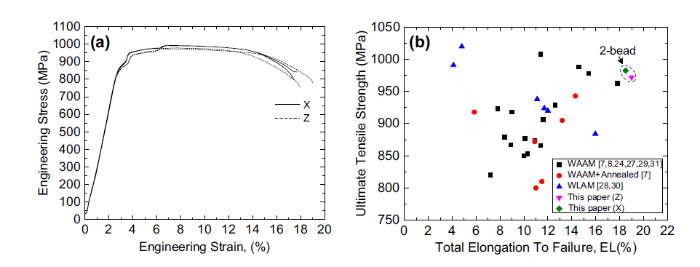

After a series of heat treatments at 650 °C for 1 h followed by air cooling, 920 °C for 3 h followed by gas cooling and 540 °C for 4 h followed by air cooling, the room-temperature tensile property was tested according to ASTM E8/E8M-16a. The engineering tensile stress-strain curves show that the alloy has a high tensile strength and high ductility, as shown in Fig. 3a. For 2-bead wall, the ultimate tensile strength (UTS), yield strength (YS) and elongation (EL) are 972.5 ± 2.5 MPa, 842.5 ± 2.5 MPa and 19.0% ± 1.0% in Z direction, and 982.5 ± 7.5 MPa, 858.0 ± 8.0 MPa and 18.5% ± 0.5% in X direction, respectively, as listed in Table 2. The UTS versus EL of the studied alloy and the referenced Ti-6Al-4V [7, 8, 24, 27,28,29,30,31] fabricated by wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM) and wire laser additive manufacturing (WLAM) are plotted in Fig. 3b. It indicates that the alloy presents a better combination of high tensile strength and high ductility. Especially, the studied alloy presents a weak anisotropy.

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

a Engineering tensile stress- strain curves of 2-bead wall, b ultimate tensile strength versus total elongation to failure for Ti-6Al-4V titanium alloy fabricated by different wire additive manufacturing processes

Table 2 Room temperature tensile properties of 2-bead wall after heat treatment

| Direction | UTS (MPa) | YS (MPa) | EL (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Z | 972.5 ± 2.5 | 842.5 ± 2.5 | 19.0 ± 1.0 |

| X | 982.5 ± 7.5 | 858.0 ± 8.0 | 18.5 ± 0.5 |

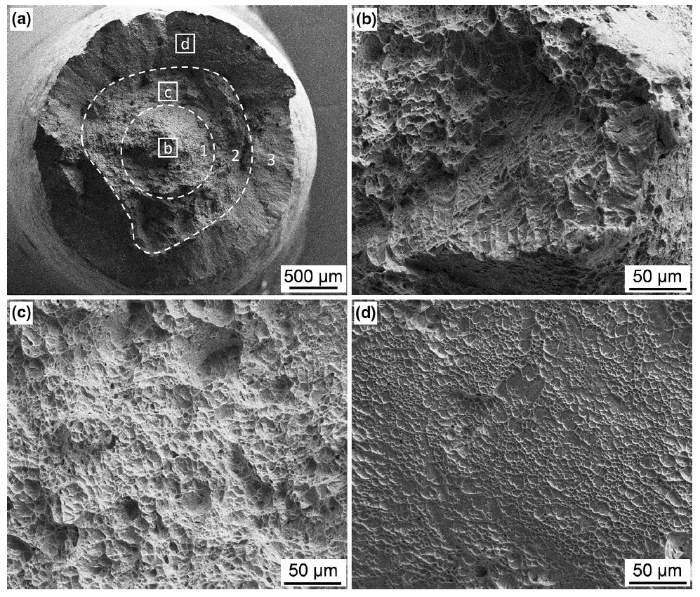

The fractured specimen has an obvious necking. The tensile fracture surface was observed. It can be found that the fracture surface includes three zones, i.e., fibrous zone (zone 1), radial zone (zone 2) and shear lip zone (zone 3), as shown in Fig. 4a. The enlarged images of the squared regions in the three zones are shown in Fig. 4b-d, respectively. The fibrous zone and radial zone present a deep dimple morphology, and the shear lip zone presents a shallow shear dimple morphology. The above features indicate that the specimen shows a typical ductile fracture.

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

SEM images of the tensile fracture surfaces for 2-bead specimen in X direction: a entire fracture surface, showing three zones, i.e., fibrous zone, radial zone and shear lip zone; b-d corresponding enlarged images of the squared regions in a

The mechanical properties of alloys are dependent on the chemical position and microstructure. The studied Ti-6Al-4V has a normal commercial composition, as listed in Table 1. Therefore, the superior tensile property arises from the microstructure.

3.2 Microstructure

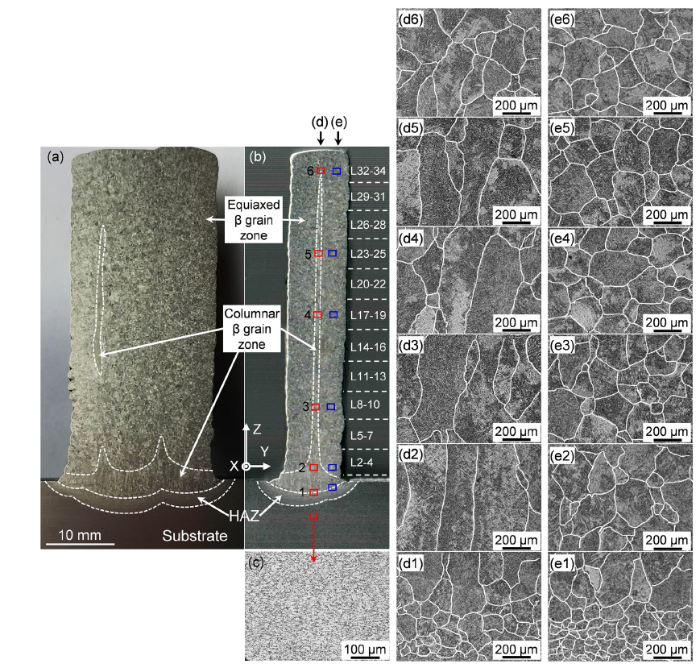

Figure 5a, b shows the optical macrographs (Y-Z sections) of 5-bead and 2-bead walls after heat treatment. It can be observed that both 5-bead and 2-bead walls are consisted of more than ~ 85% fine EGβ zone and less than ~ 15% CGβ zone. The CGβ zones are mainly located at several layers deposited in the beginning and the overlapped zones, as shown in Fig. 5a and b. Especially for 5-bead wall, only a part of one overlapped zone presents CGβ morphology.

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Optical macrographs in Y-Z sections of 5-bead a and 2-bead walls b after three-stage heat treatment, showing large regions of fine equiaxed prior β grain zones, c microstructure of the substrate, d1-d6 magnified β grain morphologies in the rectangles labeled as 1-6 in d row in b, e1-e6 magnified β grain morphologies in the rectangles labeled as 1-6 in e row in b

The magnified microstructure of the substrate is shown in Fig. 5c. It is a typical equiaxed α grain microstructure. The magnified β grain morphologies in all layers in the Y-Z section of 2-bead wall have been observed. The magnified β grain morphologies in the rectangles labeled as 1-6 in Fig. 5b are shown in Fig. 5 d1-6 and e1-6. In the heat affected zone (HAZ), the fine EGβ with a diameter of 50-200 μm forms, as shown in the lower parts of Fig. 5d-1, e-1. It means that the temperature of a part of HAZ is above the β transus during deposition process. The upper parts of Fig. 5d-1, e-1 are the bottom of the molten pool, where the β grains grow dramatically and some CGβ emerge. In the CGβ zone from the bottom to the top, the width and length of CGβ are in a range of 100-400 μm and 500-3000 μm, respectively, which is only 1/10 of that in Ti-6Al-4V fabricated by WAAM and WLAM [16,17,18,19]. In the extensive EGβ zone, the diameter of β grains is in a range of 100-400 μm, which is as fine as that in the β annealed wrought Ti-6Al-4V alloy [32, 33]. In Ti alloys, fine equiaxed β grains can be obtained by dynamic recrystallization during hot deformation or by recrystallization during post heat treatment after hot deformation. That is to say, hot deformation is necessary to form fine equiaxed β grains. For undeformed Ti alloy, when it is homogenized above β transus, the size of β grains will increase. However, when the alloy is homogenized below β transus temperature, the size and morphology of β grains will not change because grain boundary α impedes the movement of β grain boundary. In the present study, the deposited material did not be deformed. Because all the heat treatments are below β transus, the shape, size and crystalline orientation of the observed β grains reflect their as-built states.

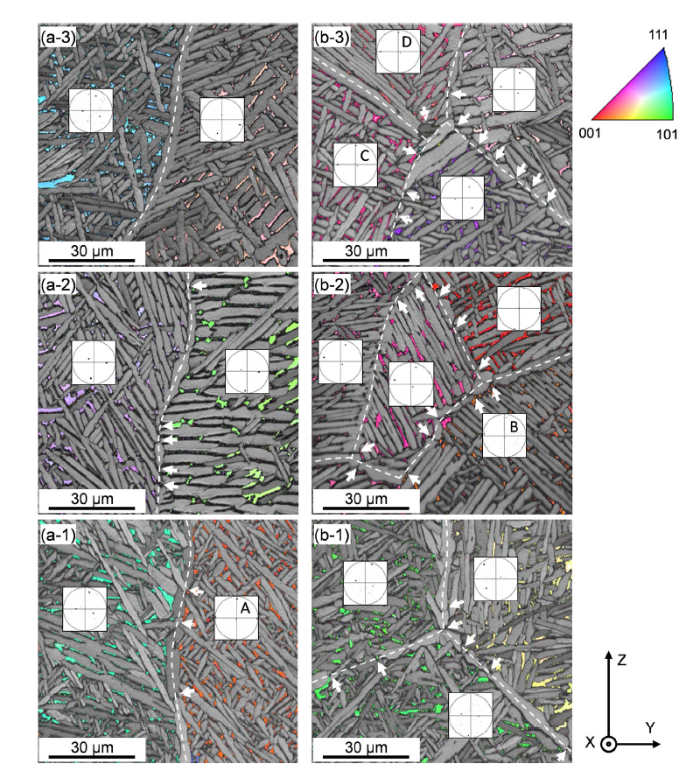

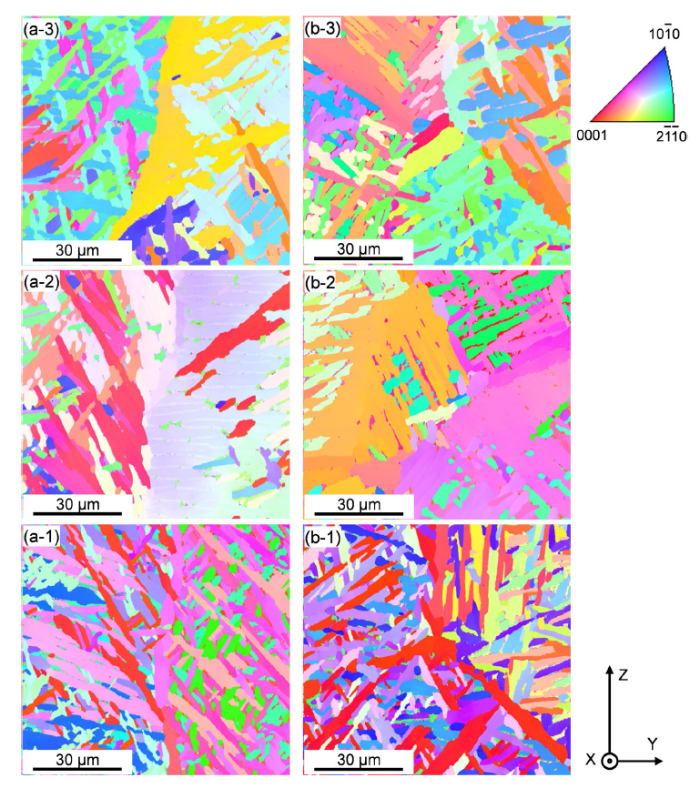

EBSD orientation maps of β phase and α phase morphology in CGβ zone and EGβ zone in Y-Z section of 2-bead wall after heat treatment were further obtained under EBSD system, as shown in Fig. 6. EBSD orientation maps of α phase are shown in Fig. 7. The (001) pole figures of β grains are labeled in each grain. It has been reported that epitaxial growth CGβ had a strong 〈001〉 solidification texture in the AMed Ti-6Al-4V alloy [11, 12]. In the present work, it has been found that 〈001〉 directions of most β grains deviate from Z direction. Only four observed β grains, i.e., grains A, B, C and D, are close to Z direction, as shown in Fig. 6. It implies that CAEBWAM technology can weaken solidification texture via promoting the EGβ formation and reducing the β grain size.

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

EBSD orientation maps of β phase and α phase morphology in Y-Z section of 2-bead wall after three-stage heat treatment: a columnar β grain zone, b equiaxed β grain zone. a-1, b-1 the 2nd layer; a-2, b-2 the 18th layer; a-3, b-3 the 32th layer. The dashed lines indicate the original β grain boundaries. The insets are (001) pole figures of β grains

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

EBSD orientation maps of α phase in Y-Z section of 2-bead wall after three-stage heat treatment: a columnar β grain zone, b equiaxed β grain zone. a-1, b-1 The 2nd layer; a-2, b-2 the 18th layer; a-3, b-3 the 32th layer

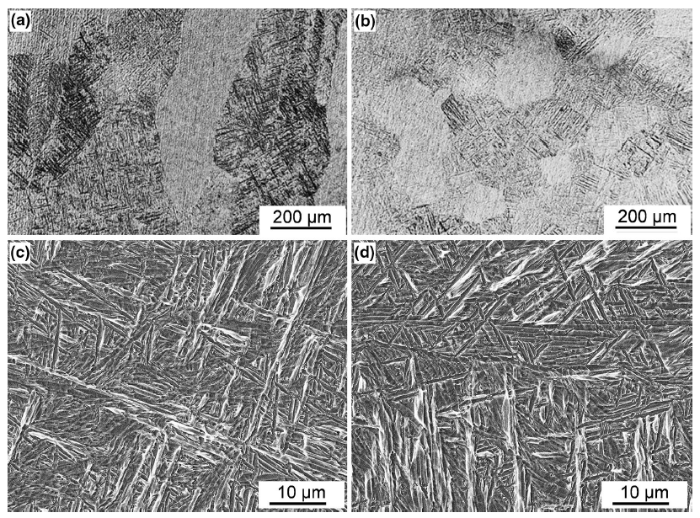

Compared to the martensitic microstructure of the as-built wall as shown in Fig. 8, the alloy shows a lamellar microstructure after heat treatment. Grain boundary α phase (GB α) locates at original β grain boundaries, as indicated by the white dashed lines in Fig. 6, and α lamellae locate in original β grains. However, different from the β annealed lamellar microstructure, most GB α is discontinuous as indicated by white arrows in Figs. 6 and 7, and intragranular α lamellae are much shorter. Such microstructure is similar to basket-weave structure, which usually possesses excellent mechanical properties.

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Microstructures of the as-built 2-bead wall, showing a martensitic microstructure: a, c CGβ zone, b, d EGβ zone, a, b optical macrographs, c, d SEM macrographs

3.3 Formation mechanism of microstructure

CAEBWAM technology has two characters. Firstly, the wire is fed inside and fully enveloped by coaxial hollow conical electron beam with a gradually distributing energy concentration. Then, the wire is uniform preheated before melting. That is to say, a less heat input is needed to melt the wire for CAEBWAM than that in conventional electron beam wire feeding additive manufacturing (EBWAM), WAAM and WLAM [17]. Therefore, the molten pool has a lower temperature. Secondly, continuous stationary transfer of liquid metal from the bottom end of wire to the deposition is reliably maintained by the “bridge” of surface tension forces. As soon as liquid metal formed at the bottom end of the fed wire touches the liquid metal in the molten pool on the deposition, a fluid neck-way is immediately formed between the bottom end of the wire and the deposition. This liquid metal flow formed and maintained under influence of surface tension forces serves as a reliable channel for smooth and steady transfer of additive material from the consumable material onto the deposition [26]. Therefore, liquid metal does not need to have a good fluidity. The molten pool is more stable, and its temperature can be lower. The above two characters indicate that CAEBWAM has a smaller G and larger R than that in conventional wire feeding additive manufacturing.

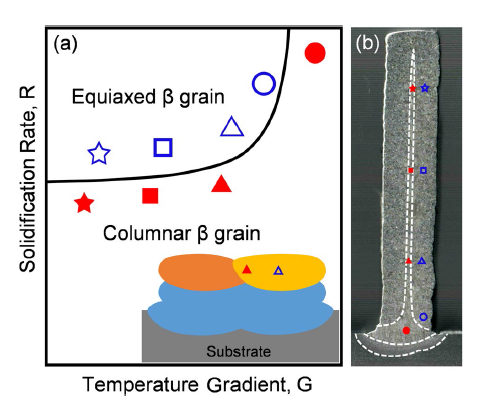

It has been known that the solidification grain morphology is determined by the G/R ratio and a large G/R, i.e., a large G or/and a small R will produce columnar grains [34,35,36], as illustrated in Fig. 9a. Thereby, controlling the G versus R during solidification could obtain different grain morphologies. In the present work, EGβ zone and CGβ zone coexist in 2-bead and 5-bead walls. It indicates that there is different G versus R in different sites for the same deposition. G versus R of the EGβ zone is located above the columnar to equiaxed transformation curve (CETC), while G versus R of the CGβ zone is located below CETC.

Fig. 9

Fig. 9

a Illustration of Ti-6Al-4V solidification map, showing that columnar β grains and equiaxed β grains can be obtained via controlling temperature gradient (G) and solidification rate (R). The different color shapes in a illustrating G vs. R in different sites of 2-bead wall during deposition in b

Furthermore, G versus R is not a constant at different deposited layers. In the electron beam additive manufacturing process, because of a high vacuum circumstance, only a small part of input heat is dissipated via thermal radiation and most heat is conducted to the former deposited layers and then to the substrate. Therefore, the temperature of the former deposited layer will raise higher and higher, which is similar to that in conventional wire feeding additive manufacturing [36]. For the several layers close to the substrate, because the substrate has a low temperature, the molten pool dissipates heat quickly, which results in both G and R at high levels. The location of G versus R in solidification map is illustrated by the red solid circle in Fig. 9a. In such a G versus R condition, β grains grow epitaxially and present a columnar morphology. Because of heat accumulation and increased temperatures at higher layers, both G and R gradually decrease during deposition.

Moreover, G and R are also different at locations within the bead and the overlapped regions on the sample layer. The deposition strategy is bi-directional. This implies that the overlapped region has a higher temperature when the electron beam travels back in the next scan track, and G and R of the overlapped zone will be smaller than those at other site.

Based on above analysis and the observations in 2-bead wall, the G versus R in different sites on different layers of 2-bead wall during deposition is illustrated using different color shapes in Fig. 9. Although the overlapped zone of 2-bead wall shows CGβ morphology, only a part of one of four overlapped zones in 5-bead wall specimen presents CGβ morphology, as shown in Fig. 5a. It indicates that G versus R can match excellently to promote the formation of EGβ even in the overlapped zone. CAEBWAM technology may become a potential method to achieve a completely EGβ morphology, which will be conducted in further studies.

The discontinuous GB α and short intragranular α lamellae arise from solid phase transformations during interpass thermal cycling and post heat treatments. Sabban et al. [37] have achieved a bimodal microstructure, which is composed of equiaxed α phase and β transformed structure, in AMed Ti-6Al-4V alloy by repeated thermal cycling close to but below the β transus temperature. A new mechanism is proposed to explain the globularization of α phase. The initial martensitic microstructure provides the necessary substructure boundaries to initiate globularization by the mechanism of thermal grooving and boundary splitting. The oscillating volume fractions of α and β phases during thermal cycling in synergism with epitaxial growth of α phase due to slow cooling rate leads to globularization. Zhao et al. [38] also achieved a bimodal microstructure and a superior ductility by a three-stage heat treatment below β transus temperature in a laser solid formed extra low interstitial Ti-6Al-4V titanium alloy. They proposed that the globularization mechanism of the α laths was attributed to the polygonization of the inherent dislocation during subcritical annealing. In the present work, similar mechanisms in interpass thermal cycling during deposition and post heat treatments result in the formations of discontinuous GB α and short intragranular α lamellae. The isotropic tensile property, high strength and ductility arise from a microstructure with fine equiaxed β grains, discontinuous GB α phase and short intragranular α lamellae.

4 Conclusion

In summary, using coaxial electron beam wire feeding additive manufacturing technology a structure composed of 2-bead and 5-bead walls of Ti-6Al-4V alloy has been fabricated, which consists of more than ~ 85% equiaxed prior β grains zone with texture free and less than ~ 15% columnar prior β grains zone. Such large region of fine equiaxed prior β grains arises from a special combination of the temperature gradient and solidification rate. Due to solid phase transformations during interpass thermal cycling and post heat treatments, discontinuous grain boundary α phase and short intragranular α lamella formed. A microstructure with fine equiaxed β grains and above α morphology makes the material have a weak anisotropy, a high strength and elongation.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the internal funding source from University of Shanghai for Science and Technology.

Reference

AbstractSelective laser melting (SLM) is an additive manufacturing technique in which functional, complex parts can be created directly by selectively melting layers of powder. This process is characterized by highly localized high heat inputs during very short interaction times and will therefore significantly affect the microstructure. In this research, the development of the microstructure of the Ti–6Al–4V alloy processed by SLM and the influence of the scanning parameters and scanning strategy on this microstructure are studied by light optical microscopy. The martensitic phase is present, and due to the occurrence of epitaxial growth, elongated grains emerge. The direction of these grains is directly related to the process parameters. At high heat inputs it was also found that the intermetallic phase Ti3Al is precipitated during the process.]]>

DOI

URL

PMID

[Cited within: 1]

Shaped metal deposition is a novel technique to build near net-shape components layer by layer by tungsten inert gas welding. Especially for complex shapes and small quantities, this technique can significantly lower the production cost of components by reducing the buy-to-fly ratio and lead time for production, diminishing final machining and preventing scrap. Tensile testing of Ti-6Al-4V components fabricated by shaped metal deposition shows that the mechanical properties are competitive to material fabricated by conventional techniques. The ultimate tensile strength is between 936 and 1014 MPa, depending on the orientation and location. Tensile testing vertical to the deposition layers reveals ductility between 14 and 21%, whereas testing parallel to the layers gives a ductility between 6 and 11%. Ultimate tensile strength and ductility are inversely related. Heat treatment within the alpha+beta phase field does not change the mechanical properties, but heat treatment within the beta phase field increases the ultimate tensile strength and decreases the ductility. The differences in ultimate tensile strength and ductility can be related to the alpha lath size and orientation of the elongated, prior beta grains. The micro-hardness and Young's modulus are similar to conventional Ti-6Al-4V with low oxygen content.

WeChat

WeChat