The structural evolution of Cu45Zr45Ag10 metallic glass was investigated by in situ transmission electron microscopy heating experiments. The relationship between phase separation and crystallization was elucidated. Nucleation and growth-controlled nanoscale phase separation at early stage were seen to impede nanocrystallization, while a coarser phase separation via aggregation of Ag-rich nanospheres was found to promote the precipitation of Cu-rich nanocrystals. Coupling of composition and dynamics heterogeneities was supposed to play a key role during phase separation preceding crystallization.

Phase separation has been observed in Pd-, Zr-, Cu-, Al-, etc.-based bulk metallic glasses (BMGs) [1] and utilized to design BMG composites [2, 3, 4, 5, 6] or to improve the plasticity [7, 8, 9, 10]. Phase separation-induced composition fluctuation was usually thought to favor nucleation or crystallization and thus deteriorate the glass forming ability (GFA) such as in Al-based system [11, 12]. It is confused that phase separation can also occur in BMG systems with higher GFA such as in Pd-based systems [13]. Until now, how phase separation influences crystallization in BMGs with high GFA remains unclear due to the lack of in situ experiments on nanometer scale. It is expected that during rapid quenching frozen-in BMG can be acquired and phase separation can be avoided, and subsequent annealing will lead to phase separation as well as crystallization. Investigating the microstructural evolution of such frozen-in BMGs during in situ heating process on a nanometer scale will help to clarify the key factor impeding crystallization and provide a new perspective for understanding the forming mechanism of phase separation-based BMGs.

Cu45Zr45Ag10 amorphous alloy is a typical BMG with a high GFA. The existence of a small positive enthalpy of mixing (+2 kJ/mol) between Cu and Ag pairs [14] implies the tendency of phase separation. However, no phase separation was observed in as-prepared BMG, and the GFA was increased from 2 mm (Cu50Zr50) to 6 mm (Cu45Zr45Ag10) by the addition of Ag [15]. In addition, adding a third element usually tends to decrease the cluster mobility, and thus the atomic rearrangement becomes difficult and crystallization can be avoided during rapid quenching [16, 17]. On the contrary, compared with Cu50Zr50 metallic glass, the atomic mobility of Ag-rich clusters in Cu45Zr45Ag10 amorphous alloy was found to be greatly enhanced via first-principle simulation [18, 19]. The improvement of GFA was proposed to result from the coupling between chemical and dynamic heterogeneities, i.e., dynamically faster Ag-rich clusters (Ag- and Zr-rich interpenetrating clusters centered by paired or stringed Ag atoms) and dynamically slower Cu-rich clusters centered by Cu atoms [18]. Therefore, by recording the crystallization process it is possible to elucidate how this kind of coupling impedes the crystallization during rapid quenching and understand the thermal stability of this amorphous alloy.

In this paper, in situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) heating experiments were carried out to investigate the microstructure evolution of Cu45Zr45Ag10 BMG. By using the designed MEMS-based in situ heating holder with high stability at high temperature, the microstructural evolution at nanometer scale was recorded. Phase separation, aggregation and further crystallization were observed in this amorphous alloy. The relationship between phase separation and crystallization was elucidated. The effects of composition and dynamics coupling on crystallization behavior as well as possible mechanism of higher GFA were also discussed.

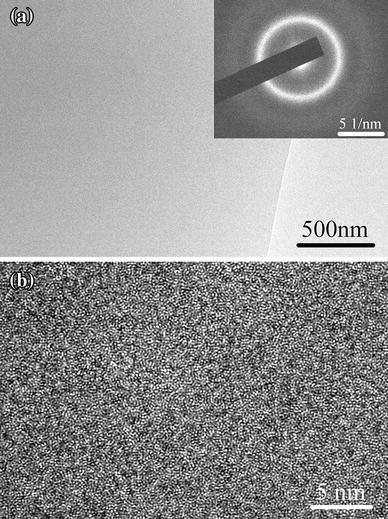

Alloy ingots with nominal compositions of Cu45Zr45Ag10 were prepared by arc melting pure Cu, Zr and Ag four times under high-purity argon atmosphere. The ingots were then re-melted and injected into a copper mold to form a rod with a diameter of 3 mm. Slices with a thickness of 0.3 mm were cut from the rod perpendicularly, mechanically polished to about 80 μ m, and then electrochemically polished till perforation with nitric acid and methanol mixture with a volume ratio of 1:3 at a temperature of -30 ° C. The thinnest area was further cleaned using a Gatan PIPS ion miller at a low voltage of 2.8 kV for 10 min. Then, the specimen was characterized by TEM. The bright field (BF) image in Fig. 1a shows a homogenous contrast, and the high-resolution electron microscopy (HREM) image in Fig. 1b shows a maze-like pattern, typical of the amorphous structure. The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern in the inset of Fig. 1a shows a halo ring without any detectable diffraction spots.

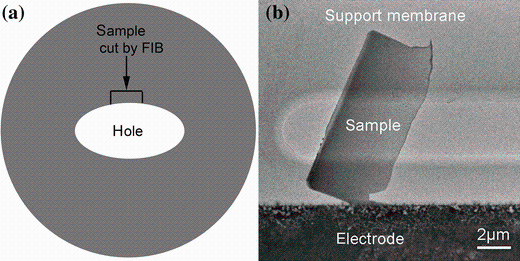

Then, a lamella with a size of 5 μ m × 10 μ m close to the hole was cut using a focused ion beam (FIB) system (FEI Dual Beam Strata DB235) as shown in Fig. 2a. In order to avoid Ga ion irradiation, the thinnest area of the lamella was only scanned three times with an ion beam aperture of 10 pA, while the cutting was performed with an ion beam aperture of 50 pA. Then, the lamella was transferred onto the in situ heating chip with an ex situ nanomanipulator. Figure 2b shows the TEM image of transferred sample on the support membrane. This method provides a thinner sample than the FIB “ lift-out” lamella and avoids the damage from Ga ion irradiation largely. Further in situ heating experiments were carried out on a monochromated FEI Tecnai F20ST/STEM microscope (200 kV). The in situ heating holder was designed to minimize the drift at high temperature so that the images at high magnification can be recorded. The heating rate was 20 K/min. When a new phenomenon was observed during the heating process, heating was paused for image recording.

| Fig. 2 a Preparation scheme of TEM sample cut by focused ion beam from the electrochemically polished sample, b the sample transferred onto the in situ heating chip by an ex situ nanomanipulator |

Compared with in situ heating experiments via X-ray or neutron diffraction [20, 21, 22, 23], in situ TEM experiments can provide more intuitive information on the nanometer scale [24]; especially by acquiring high-angle annular dark field (HAADF) images combined with energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectrum, composition information can be retrieved simultaneously. Therefore, HAADF images (which were also called Z-contrast images) were used to record the microstructure evolution during heating process. The relationship between the intensity of HAADF images (I) and the atomic number (Z) [25] can be described by the equation

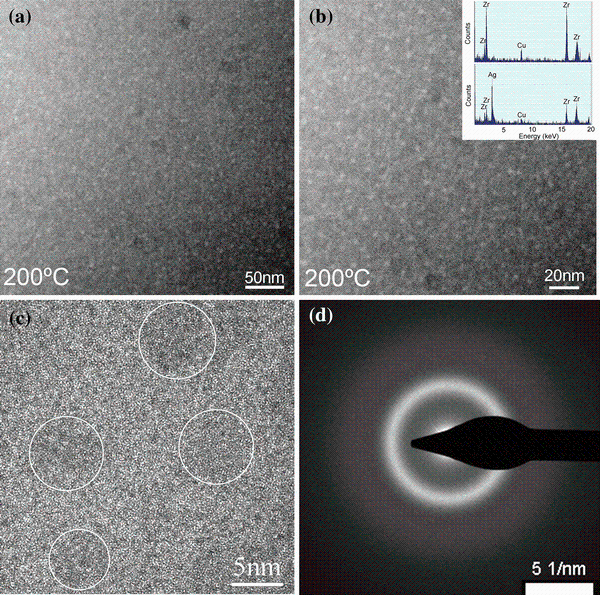

When the sample was heated to 200 ° C, small bright spheres with a diameter < 5 nm occur (as shown in Fig. 3a, b). Since there is an overlap between the bright spheres and the matrix along the thickness direction, the quantitative information could not be retrieved; still the tendency from the EDX spectrum (shown in the inset of Fig. 3b) can be concluded that the bright area is rich in Ag and Zr, while the dark matrix is rich in Cu and Zr. This is quite consistent with the contrast in HAADF images. Since the atomic numbers of Cu, Zr, Ag are 29, 40 and 47, the bright spheres should contain more heavier Ag atoms, and the dark areas contain more lighter Cu atoms. The HREM image in Fig. 3c shows that although there is a slight contrast difference between the Ag-rich nanospheres and the matrix, both areas remain amorphous structure. And the SAED pattern shows a typical halo ring without any detectable diffraction spots (shown in Fig. 3d). In phase-separated Zr56-xGdxCo28Al16 (x = 10, 20) amorphous alloys, the SAED patterns can well reflect the two halo rings resulted from Zr-rich and Gd-rich amorphous areas [26]. However, in our case, only one halo ring was observed. According to our ab initio molecular dynamics simulation results, the partial pair distribution functions of Ag and Cu exhibit the peaks at 0.272 and 0.288 nm, separately. Such a smaller difference cannot be distinguished in the broad halo ring of the SAED patterns.

According to the above experiments, the phase separation happens at 200 ° C and the Ag-rich regions exhibit droplets like morphology; therefore, the mechanism of phase separation in Cu45Zr45Ag10 amorphous alloy can be attributed to nucleation and growth mode rather than spinodal decomposition, which was further elucidated based on the following discussion. Firstly, in the initial stage of phase separation, the typical morphology shows a homogeneous distribution of spherically droplets in the matrix for the nucleation and growth mode, while it is an interconnected type of structure for spinodal decomposition. Secondly, from the free energy point of view, nucleation and growth-induced phase separation are a metastable state, minor perturbation will increase the free energy, and thus, an energy barrier exists. A slightly higher temperature 200 ° C provides the necessary energy to overcome the energy barrier for the occurrence of such phase separation. On the contrary, spinodal decomposition proceeds spontaneously to reduce the free energy regardless of the temperature.

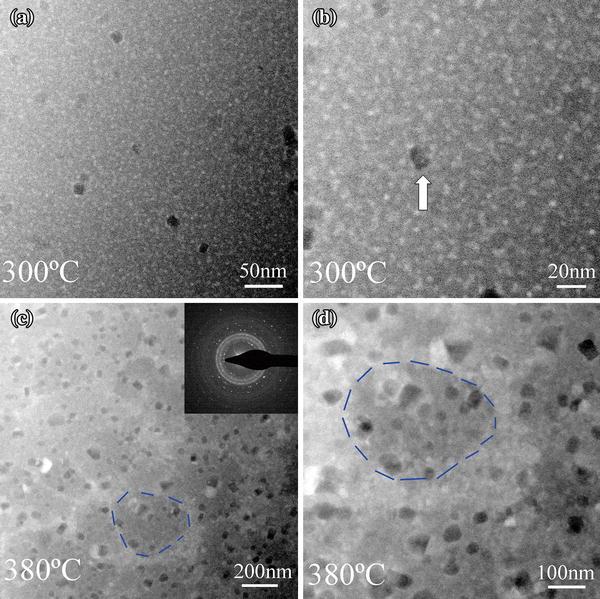

When the temperature was increased to 300 ° C, the density of Ag-rich spheres increased, while the size of these Ag-rich spheres does not change significantly and remains below 10 nm (in Fig. 4a, b). Some collision and coalescence between Ag-rich spheres occurred. At the same time, a few Cu-rich nanocrystals precipitated, as concluded from the darker areas in the images, which was indicated by the bright arrow in Fig. 4b. Even if the temperature was kept at 300 ° C for one hour, no more Cu-rich nanocrystals precipitate out from the matrix obviously. Based on the observation that these Cu-rich nanocrystals are surrounded by Ag-rich nanospheres, it is suggested that the homogeneously distributed Ag-rich nanospheres inhibit the growth of Cu-rich nanocrystals. In Cu45Zr45Ag10 metallic glass, there exists small positive enthalpy of mixing between Cu and Ag, which leads to the coupling of dynamically faster Ag-centered clusters surrounded by more Zr atoms and dynamically slower Cu-centered clusters surrounded by more Cu atoms [18, 19]. According to our TEM results, the critical temperature of phase separation (200 ° C) was far below the glass transition temperature (Tg); therefore, liquid phase separation can be avoided during rapid quenching. By carrying out a post-annealing treatment, the atomic-scale coupling between composition and dynamics heterogeneities seems to favor the occurrence of phase separation. Given a typical thermal energy, Ag-rich clusters with a higher mobility tend to form nanospheres and the growth of Ag-rich nanospheres is geometrically confined by the Cu-rich clusters with lower mobility. And at the same time, even if a few Cu-rich nanocrystals precipitated out from the matrix, their growth was impeded by the surrounding Ag-rich nanospheres.

However, when the temperature was increased to 380 ° C, aggregation of Ag-rich nanospheres occurs and forms the bright interconnected areas, leaving behind the darker Zr and Cu richer islands of 100-250 nm in diameter. At the same time, Cu-rich crystals in size of 10-30 nm precipitated quickly from the remaining Cu-rich amorphous matrix (in Fig. 4c, d) in one minute. The corresponding SAED pattern (shown in the inset of Fig. 4c) indicates that the crystallization occurs. Interestingly, the aggregation of Ag-rich nanospheres happens in a manner similar to grain boundary segregation in crystalline alloys, as schemed by the blue broken lines in Fig. 4c, d. Because the rapid precipitation of Cu-rich crystals and aggregation of Ag-rich nanospheres happen almost simultaneously, we could not retrieve the sequence of these two processes experimentally. Since the homogenously distributed Ag-rich nanospheres were proposed to impede the precipitation and growth of Cu-rich nanocrystals at 300 ° C, it was suggested that the precipitation of Cu-rich nanocrystals becomes much easier in the remaining Cu-rich amorphous matrix after the aggregation of Ag-rich nanospheres. The aggregation of Ag-rich nanospheres is proposed to result from the increased mobility due to a drastic decrease in viscosity of the amorphous matrix near the glass transition temperature and can be viewed as a sign of glass transition. In fact, the aggregation of crystalline copper globule dispersed in as-prepared Fe-Zr-B-Cu amorphous alloy was also used as an indication of a glass-to-liquid transition [27]. The heating process was paused to record HAADF images at some typical stages; this may lead to a lower glass transition temperature (Tg, 380 ° C) than the measured Tg (410 ° C) with differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) at a heating rate of 20 K/min [28].

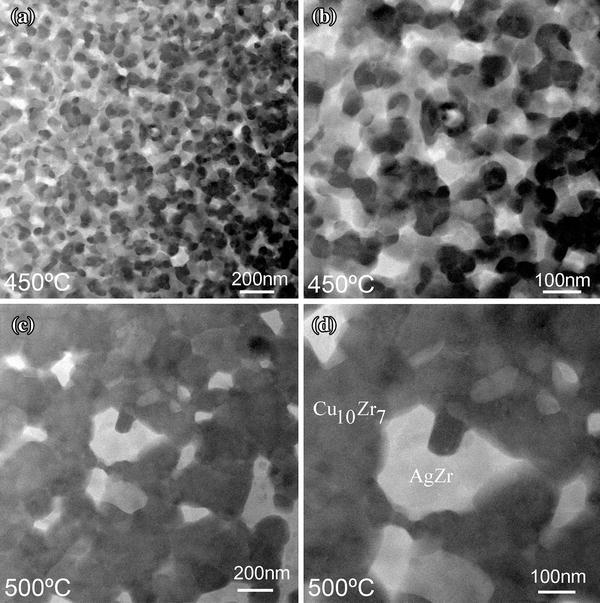

At 450 ° C, aggregated Ag-rich nanospheres grow and form a network-like structure (in Fig. 5a, b). Cu-rich crystals with a size around 50-100 nm were surrounded by the framework composed of Ag-rich crystals. Growth and soft impingement of Cu-rich and Ag-rich crystals happen. Although soft impingement also limits the growth of nanocrystals, the spatial distribution of Cu-rich and Ag-rich areas was considered to be the key role preventing further crystal growth at 450 ° C since the atomic long-range diffusion was greatly limited geometrically. At 500 ° C, coarsening of crystals Cu10Zr7 and AgZr becomes evident (as shown in Fig. 5c, d). Interconnection between Cu10Zr7 crystals happens and AgZr crystals become isolated gradually.

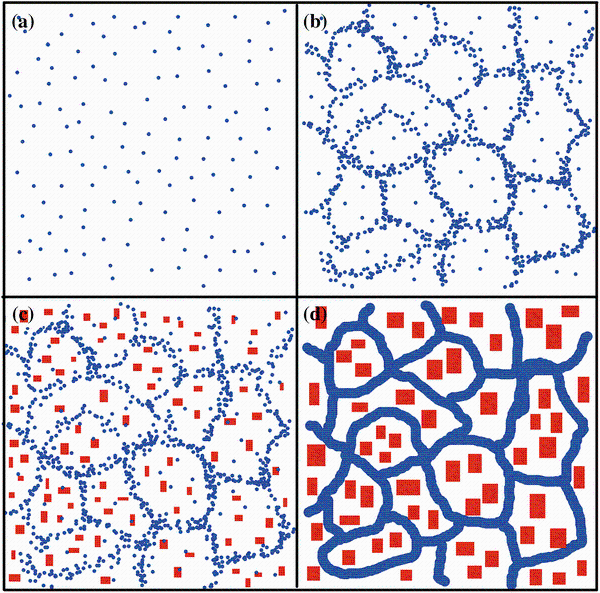

Figure 6 shows a scheme of the microstructure evolution in the Cu45Zr45Ag10 amorphous alloy. With the increase in temperature, phase separation into Ag-rich nanospheres occurs firstly at 200 ° C, and then Ag-rich nanospheres aggregation occurs at 380 ° C near the glass transition temperature. Afterward, Cu-rich nanocrystals precipitated quickly from the remaining Cu-rich amorphous matrix. Then, the Ag-rich area becomes crystallized forming a network-like structure, impeding the further coarsening of Cu-rich nanocrystals. Finally, growth and coarsening occur at higher temperature. In general, phase separation-induced composition fluctuation may destabilize the thermal stability of amorphous alloys and provide the chemical composition suitable for crystallization, and therefore, GFA may be deteriorated in phase-separated BMG systems. However, our experiments show that nanoscale phase separation at early stage impedes nanocrystallization in Cu45Zr45Ag10 BMG, while after the aggregation of Ag-rich nanospheres, a coarser phase separation occurs, and the precipitation of Cu-rich nanocrystals becomes easier. Therefore, there are two energy barriers of phase separation and subsequent Ag-rich nanospheres aggregation to overcome before crystallization in this amorphous alloy can happen. Thus, the coupling of composition and dynamics heterogeneities is believed to be the key role in dominating the nanoscale phase separation at early stage and is the microstructural origin of higher GFA. It is suggested that in Pd-based metallic glass with higher GFA, similar phase separation and crystallization behavior may also exist, which needs further investigation [13].

In conclusion, by carrying out in situ TEM heating experiments, the microstructural evolution of Cu45Zr45Ag10 amorphous alloys was revealed. The relationship between the phase separation and crystallization was clarified. Nanoscale phase separation at the early stage was seen to impede crystallization, while a coarser phase separation via Ag-rich nanospheres aggregation, in a manner similar to grain boundary segregation in crystalline alloys, was found to favor the precipitation of Cu-rich nanocrystals. These results may shed light on the crystallization mechanism in phase-separated BMGs with high GFA and provide information for BMG design with high stability based on phase separation.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51101004). H. Wang is grateful for the financial support of China Scholarship Council. Z.Q. Liu is grateful for the support by the IMR SYNL-T.S. Kê Research Fellowship.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

| [1] |

|

| [2] |

|

| [3] |

|

| [4] |

|

| [5] |

|

| [6] |

|

| [7] |

|

| [8] |

|

| [9] |

|

| [10] |

|

| [11] |

|

| [12] |

|

| [13] |

|

| [14] |

|

| [15] |

|

| [16] |

|

| [17] |

|

| [18] |

|

| [19] |

|

| [20] |

|

| [21] |

|

| [22] |

|

| [23] |

|

| [24] |

|

| [25] |

|

| [26] |

|

| [27] |

|

| [28] |

|